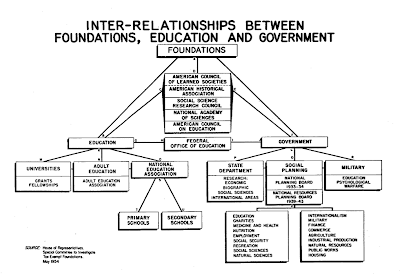

Your goverment in pictures, 1954

An authentic historical document:

Doesn’t look much like what you learned in 9th-grade civics class? There’s a reason for that. As you know, of course, dear UR reader, you’ve been rather pwned.

In terms of actual control over government decisions, the present state of representative democracy in USG and its satellites reminds the historical observer of nothing so much as monarchy in middle-to-late decline, nowhere near absolute but still not quite ceremonial. The British monarchs of the 18th and 19th centuries might be a fair comparison.

These so-called kings and queens, from Anne through Edward VII, retained prerogative authorities in theory and were in fact quite jealous of their theoretical powers, but had become convinced that they would lose both contest and authority in any serious conflict with ascendant Whiggery. (Edward VII, to be fair, was a real figure in foreign policy—or at least so Whitehall let it be known.) When they did impact the course of government, the royal interventions tended to be symbolic, informal, and above all negative—as all weak authority is. But in reality, power depends on both habit and confidence, and somewhere around 1936 it disappeared entirely. The celebrity monarch remains, chiefly to ensure the position is not actually filled.

But since the Great Wheel has no beginning or end, democracy too must go under the bus. Indeed in Europe it is already a speck in the rear-view mirror. The idea that spontaneous popular sentiment should influence public policy is, on the Continent and increasingly in England, a fringe belief. On its face it seems absurd, as of course it is—just as if Prince Charles were to demand his titular authority. As with anything, the capacity for government is the combination of aptitude and experience. Quite plainly, Prince Charles has neither the aptitude to rule, or the experience. His coup would therefore be a joke.

Just the same can be said of the modern democratic electorate. Across centuries of throne and altar, the People grew strong; their princes, sapped by luxury, flattery and philosophy, weak; the strong seized their chance; the People pulled their princes down. And grew weak in their turn. Now the course of empire proceeds without them—to an extent they can barely imagine. By far, the American voter is the strongest left. But this isn’t saying a lot.

For a weak prince, too, may feel himself a King. His ministers butter him assiduously. “Yes, your Majesty.” “Quite right, your Majesty.” “Of course, your Majesty.” “It will be done, your Majesty.” Indeed, when I look at the Tea Party Republican of 2010, I think of the late Merovingians—like Clovis IV, 13-year-old “king of the Franks.”

Take America back! Restore the Constitution! Dear Lord. The Constitution was dead before his parents were born, and the average tea partier, even the superlative tea partier, immersed to the gills in his reality show, knows the real Washington about as well as he knows the Tang Dynasty. In fact, he probably knows the Tang Dynasty better—he knows there’s such a thing as the Tang Dynasty, and nor does he confuse it with the Wu-Tang Clan.

I once had a conversation with Larry Auster, perhaps America’s most perspicacious nationalist today, in which Auster inadvertently revealed the fact that he believed the President could have a Foreign Service officer fired. Take over Washington! 13-year-old Clovis IV had a better chance of unseating the Mayors of the Palace. At least he knew who they were. Heck, if he’d called an emergency court meeting and just walked up to his Uncle Pepin and sliced him in the neck, the Merovingians might well be kings of the Franks to this day. Audacity conquers all.

Of course, Washington has no neck. It has a thousand necks, or maybe a hundred thousand. The picture above makes it look like there’s a neck to slice. Perhaps in 1954 there almost was. It is no longer 1954. No state is incurable—but ours needs a trained surgeon and a full operating room, or perhaps an army with naval artillery support. Not an adolescent with a gilded dagger.

Why would they give Clovis IV an actual weapon? His voice cracking and his young balls swelled, he draws his royal sword for the first time, swears a terrible oath, and leaps at his obnoxious, conniving uncle—who simply smiles and presents his throat. The blade is made of gold foil. It folds up like a newspaper. Everyone laughs. The king of the Franks, scarlet-cheeked, rushes off to his chambers, cranks up a Def Leppard album and resumes his neurotic pimple excavation. History is not on his side.

But once, things were different. Once, men resisted. Once they had real swords.

There is a word in the American political vocabulary for the last struggles of meaningful representative democracy. The word is “McCarthyism.” McCarthyism, in neutral language, is the irrational belief that unelected and/or extra-governmental officials should be responsible to elected officials. The question of McCarthyism was whether the American people, by electing a Congress, could hold such august, bipartisan, professional and apolitical agencies as the State Department responsible to their fickle, uninformed wills. The answer, as it turned out, was no. Clovis IV turned bright red, sulked and went to his room.

Of course, the actual actors in “McCarthyism” were not the politicians. No one could possibly confuse a McCarthy, a McCarran, a Mundt, for Pitts and Gladstones and Disraelis. Rather, the few, bold, doomed crusaders were the staffers of the “McCarthyist” investigating committees—the notorious HUAC, the little-known and far more effective McCarran Committee, and today’s source (and my personal favorite)—the Reece Committee. These men were real warriors. You may know the name of the most notorious—Roy Cohn. Most are quite anonymous—like Rene Wormser, chief counsel of the Reece Committee, author of Foundations: Their Power and Influence.

Not that our warriors won, or had any chance of winning. They had subpoena power, however, not to mention genuine prewar educations. One of Wormser’s assistants, Kathryn Casey, actually got to read the original minutes of the Carnegie Endowment from 1909, though she didn’t get to copy them or take them home. Apparently the experience permanently affected her sanity—which should come as no surprise to the UR reader. The first half of the 20th century was, like the Elizabethan era, something of a golden age for conspiracy.

Needless to say, in 2010 the thought of Congress seriously investigating the State Department, let alone the Carnegie, Rockefeller and Ford Foundations, brings us straight back to Clovis IV. Repeating the work of the Reece Committee is not just inconceivable, but also useless. The fire has been burning quite nicely for well over 50 years; to drench the gasoline-soaked rags is not to extinguish the conflagration, let alone to rebuild the building. The tea partiers could abolish all these institutions tomorrow, not that they will, and not get the America of 1923 back.

But as students of history, we want to know how the flames started and spread. How fortunate for us that, 50 years ago, America elected a batch of know-nothing Republicans, who hired bitter, unhinged right-wing lawyers, who knew whose closet to subpoena for a skeleton or two. They knew they were walking through fire for nothing; they did; they got nothing for it. But we got their work.

The especially dedicated UR reader may enjoy the 4-volume Reece Committee transcripts—vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 4. Many parts of these read like a movie script, chiefly due to the ridiculous and disruptive antics of Wayne Hays. I have been exceptionally busy and have not had time to read the whole thing, but you can. For a study of how the American postwar university, then the entire society, got gleichgeschaltet on the ideology of the great foundations—Foundationism, we might even call it—I recommend the testimony of Professors Rowe and Colegrove in volume 1. There is also Mr. Wormser’s book linked above, a lucid and straightforward summary.